A search for truth behind “Napalm Girl”

A new documentary explores who really took one of the most iconic photos of war. And why that matters.

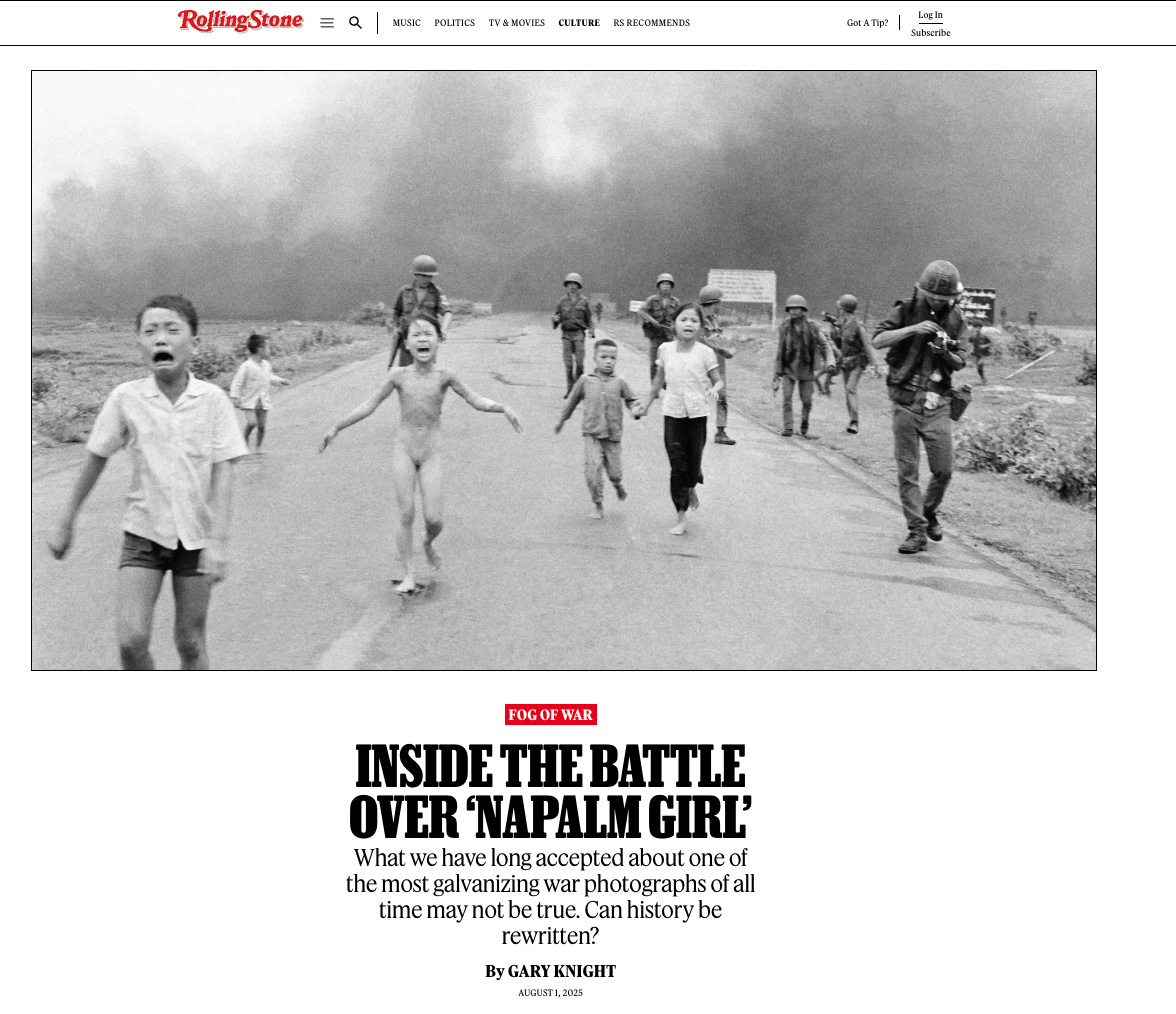

It is one of the most important photographs of war ever taken.

It is sometimes referred to as “The Terror of War,” and more informally as “Napalm Girl.” You probably have this searing image filed away somewhere in your memory: A naked 9-year-old, Vietnamese girl is running down a road in terror after a napalm attack on her village. It was taken in 1972 and the image received the Pulitzer Prize and World Press Photo awards. It shocked the world and in some ways galvanized opposition to the war.

Nick Ut, an Associated Press staff photographer, was credited for the photo and won international acclaim for capturing this iconic moment. But a new documentary titled The Stringer makes the claim that the photograph was not taken by Ut, but by a Vietnamese freelance photographer named Nguyen Thanh Nghe. It is a powerful film that sets out on a journey toward the truth about who took this photograph, and why that matters, more than a half century later.

The investigative documentary premiered earlier this year at the Sundance Film Festival, and it was directed by the award-winning film maker Bao Nguyen, the internationally renowned photojournalist and co-founder of VII Photo, Gary Knight, and the acclaimed news producer Fiona Turner. These storytellers came to Martha’s Vineyard for a screening, and I had a chance to watch the film with them and ask them questions at a public forum.

Nguyen, a Vietnamese-American filmmaker and cinematographer whose work includes highly acclaimed documentaries such as The Greatest Night in Pop (2024) and Be Water (2020) said this story of The Stringer challenged him in new ways and forced him to take risks.

He explained that his parents were around the same age as Kim Phuc, the subject of the controversial photograph. They lived along the 17th parallel, which was a frontline in the war, and where Phuc’s village was located. They were refugees of the war, like Phuc, who is still alive and working with the United Nations. When Nguyen’s parents came to the U.S., they felt that their story, and the story of the war, were told for them, he said. They were not able to bring their voice or have anyone who represented them as the narrator of the war.

“Whose story, whose memory has more value than another person?” Nguyen asked.

The film posed an almost existential risk for Nguyen, who said he had long looked up to Ut in the Vietnamese-American creative community, and that he hesitated to question the provenance of the photograph. They both live in Los Angeles now. In some ways, Nguyen explained, he wondered if it really mattered who took the photograph, if that was important when the impact of the photograph was so incredibly strong, and served to galvanize the antiwar movement.

But as he began to explore the question of authorship, and whether correcting the record of who took it really mattered, he came to feel that it did, and realized he had an extraordinary opportunity to provide a platform for a Vietnamese photographer who’d lived in obscurity and in many ways been denied his memory and experience. It mirrored the way his parents felt, on some level, he said. For so long, people like Kim Phuc and his parents, he said, were asked to purely endure and survive, rather than have the ability to bear witness and to create the narratives that tell the story of the war they lived through.

“I think the power to witness, it shouldn’t be seen as a privilege,” he said. “It should be seen as a right, a human right.”

Knight, the photojournalist at the center of this journey and the hard questions that come with it, said he first heard in 2010 about the allegation that a Vietnamese stringer, rather than Ut, took the famous photo. It always nagged at his conscience and spoke to his lived experience where he has seen so many freelance photographers, particularly local photographers from the countries being covered, have had their work appropriated, or insufficiently credited.

Twelve years after he first heard the rumors, Carl Robinson, who had been the AP photo editor in Saigon when the photo was taken, reached out to Knight and said he knew the real story and wanted to unburden himself after all these years.

Robinson, who was with AP from 1964 to 1975, is a key source in the film. He said he received the film from a stringer on June 8, 1972, during an attack on a village where the stringer was shooting as was AP staffer Nick Ut. AP bought the roll of film from the stringer for $50. When it came time to credit the photo, Robinson said he was overruled by Horst Faas, AP’s legendary Saigon chief of photos, who himself had won the Pulitzer Prize for photography. Robinson said he was instructed by Faas to credit the image to staff, which means a photo is taken by a staff photographer, and specifically to credit Ut. Faas was said to have looked out for Ut whose older brother, Huynh Thanh My, was a former AP photographer who had been killed on assignment in 1965.

After so much time, to say that a stringer took the photograph that had long been credited to Ut was an extraordinary allegation, and when he became aware of the controversy, Knight joined forces with Turner, who is his wife, and set out to track down the stringer, Nguyen Thanh Nghe. . Knight felt it was a story for the written word, but Turner felt the story needed to be told visually. So the two set out with Director Bao Nguyen to make the film along with a team that included colleague, television news producer Terri Lichstein. The first part of the journey was to find the stringer, who appears in still photographs on that day along the road where the photo was taken.

“I could see that if these allegations were true, then this was a story that was larger than one man’s story,” Turner said in the panel discussion. “It was a story that reflected a culture of the time, and how that impacted the Vietnamese journalists of the time, who were largely overlooked, and it was the American media, the Western-run media, who helped sway and determine how these narratives were told.”

Like the director Nguyen, Knight also felt a personal connection in making the film. I have worked with Gary on assignments over the last 20 years in Afghanistan, Iraq, Egypt and Myanmar and elsewhere, and I have witnessed his dedication to the craft of visual storytelling and seen that he has always had a strong affinity for and gratitude to local stringers he’s worked with across the world.

Being a stringer is a “fragile existence,” he said. Stringers often can’t afford the benefit of bulletproof jackets, helmets, and insurance. They often can’t get on a plane and go home to a safe place. They live the war.

“They often weren’t credited, as you see here,” he said. “This is not an isolated incident.”

And even with digital technology, Knight said, this still happens. He pointed out that the work of Palestinian photographers in Gaza is often challenged for its authenticity, he said, in ways that Western photographers are not. It happens everywhere in the world where stringers work.

“They can be arrested. They can be incarcerated. Nobody is going to come and rescue them and take them out,” Knight explained.

Knight knew AP’s Saigon chief of photos Faas, and worked with him in Vietnam in 2005 training Vietnamese journalists. “Like all of us, he’s capable of doing great things, generous things, good things, and making mistakes, so I hope that this film doesn’t serve as a condemnation of Horst and everything that he did, because he doesn’t deserve that,” Knight said in the dialogue after the film. Faas passed away in 2012.

I never met Faas, but I have worked alongside AP colleagues for decades and have tremendous respect for the organization. In the spirit of full transparency, I should say that over the last six months, I had collaborated with some of AP’s senior team in helping them to launch a non-profit initiative called the AP Fund for Journalism. It is sometimes said that AP sets the standards on setting standards, and I have always found that to be true. I am no longer directly involved with the APFJ, but AP’s work and its standards feel more important than ever in an age of misinformation and disinformation.

The strength of this film is that it allows viewers to make their own decisions, Nguyen said. “History belongs to everyone, but I think it’s sometimes the people that we decide to listen to.”

The film provides solid forensic evidence to shape a careful recreation of what happened on that road by using old satellite images as well as the footage of television news crews that were filming the incident as it happened. Based on this approach to documenting the moment in time, it appears that a figure on the road with a camera around his neck, who eyewitnesses identify as the stringer Nguyen Thanh Nghe, would most likely have taken the photograph. They also found Nghe, who had been living in relative obscurity, and interviewed him and his family, and he maintains that he did indeed take that image on that day and offers an explanation as to why he never spoke out publicly.

There is another important finding: the negative of the photograph appears consistent with a Pentax camera. Nghe used a Pentax, and Nick Ut typically used a Leica and has been quoted in the past saying it was a Leica camera he was using on that day. In its internal investigation, AP, however, points out that Nick Ut also owned a Pentax which had been given to him by his late brother.

To say that this film is contentious in the world of photojournalism is an understatement. It is a third rail. The Associated Press, which produced a 95-page report based on its own internal investigation, said that it found no evidence that Ut didn’t take the photograph or that the credit should be changed. Ut has consistently maintained that he did take the photograph and AP has stood by him while these questions were raised but AP also said it “remains open to the possibility that Ut did not take this photo.”

In June, NPR reported that Ut’s attorney, Jim Hornstein, planned to file a defamation lawsuit. Meanwhile, World Press Photo suspended authorship attribution of the photo, pending further evidence. In one of the finer moments of the film, it is suggested that Ut is in many ways also a victim here, as he did not choose to be credited with the photo and that it was his boss who insisted he was the one who took it. Knight’s questioning of Robinson as to why he did not object and set the record straight feels very human, and there is no reason why all these years later Robinson would benefit from revealing what he knew.

Right now, the film is being screened at festivals, but soon, hopefully, it will be released more widely. The filmmakers say they are in advanced discussions for distribution. The Stringer is likely to be available to the public later this year. And when that happens, readers of this column and those who care around the world will decide for themselves. The world needs to see this film and understand that the credit for who took this iconic photograph matters.

Watch the full panel discussion with the creators of The Stringer here.